‘The way Puerto Rico was, it’s not anymore’

Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico as a high-intensity Category 4 on Sept. 20, 2017. It was one of the deadliest hurricanes in U.S. history, and the worst natural disaster affecting Puerto Rico in almost 100 years.

The storm devastated the island’s energy grid, roads and bridges. It caused the largest power blackout in U.S. history and the second-largest in the world. More than 160,000 homes were damaged or destroyed. Most people had no access to clean water.

But in the months that followed, it was clear Maria took much more.

Almost 3,000 deaths in Puerto Rico have been linked to Hurricane Maria, according to a government-sponsored independent investigation by the George Washington University Milken Institute of Public Health that focused on hurricane-related deaths.

The hurricane continues to take its toll on Puerto Rico’s economy and on residents’ mental and emotional health. In April, a new study showed that 1 in 4 Puerto Rican schoolchildren showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder following Maria.

Carlalynne Melendez works with children in the Naguake indigenous community in the mountains of Puerto Rico.

“If there’s a wind blowing in a classroom, the students are afraid,” Melendez said. “ ‘Miss? Maria. It’s coming,’ they say.

“They’re still traumatized. It’s what they call post traumatic shock. They’re still suffering from it, after losing parents, losing family members.”

The George Washington University report noted that the island lacked an updated emergency communication plan. The storm knocked out cable service and telephone lines, destroyed cellphone towers and severed internet cables.

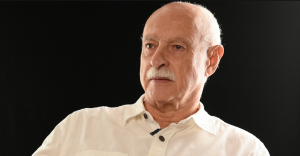

Journalist Rafael Matos recalls closed airports, no electricity, scrounging for food. His wife and daughter were visiting Miami when Maria hit, and they weren’t able to return to Puerto Rico for four months.

Matos was used to working late at night, but with no electricity, he went to bed at 8. “Sometimes,” he said, “you didn’t even know what day it was.”

“Our whole communication systems collapsed alongside the electrical system,” he said. “We were like back in the pioneer days, I guess, to use an American word. We were living daytime only.”

Matos lost his collection of old newspapers, books and films – “all my references in life.”

Matos was a combat medic during the Vietnam War. “I was out there in the field picking up the dead and the wounded, so mentally, I was prepared for all this stuff. But what really depressed me was the fact that there was no communication. My family, up in the States, did not know what had happened to me.”