Article, graphic, video, photos By Devna Bose

AGUADILLA, PUERTO RICO —

In September 2017, the winds blew hard on an island on the edge of the Caribbean Sea.

And when the thunderous rain and gales passed, Puerto Ricans found that they were left as bare as the land they love.

Hurricane Maria immediately devastated the island’s infrastructure and landscape, but in the months that followed, it was clear that she took more than just that.

Rochelle Desiree Mermelstein Gomez thought about killing herself three times after the storm.

The first time was after she discovered the extent of damage on her home post-hurricane. When Rochelle first stepped outside of her home following the storm, she discovered a number of trees that were uprooted in her yard. At the time, she was sleeping three hours a night, and the smell of rain was still fresh on the ground. The daughter of a disabled mother and parent to a farm of animals, Rochelle felt helpless.

“I thought, ‘How am I going to lift or cut some of the branches?’” she said. “I tried my best, but I can’t, and at that moment, I started crying.”

She found a knife and thought to herself that it would be easy. It had been a week since the storm dissipated.

But just then, a group of volunteers came to her door with chainsaws to help clear the destruction decorating her front yard.

“They saved my life, because if they didn’t show up, I would have probably killed myself in that moment,” she said.

At the Línea PAS crisis hotline center in Bayamon, the phones ring every few minutes.

Right after the hurricane struck, however, the echoing chime of phone calls was endless.

The calls were urgent and desperate, detailing stories of the loss of homes, loss of families, loss of everything, said Suzanne Roig Fuertes.

“We knew that the loss of whatever is the main cause of suicide, but this is a loss of everything,” she said, of the hurricane. “It’s a loss of community.”

A thousand calls a day, at first. Now, there are still 500 to 600 calls a day — cries of help from people who have no money or who suffer from mental illness resulting from the hurricane and are considering suicide.

Fuertes is the administrator of ASSMCA, the Administracion de Servicios de Salud Mental y Contra la Adiccion in Bayamon, Puerto Rico, about 20 minutes south of San Juan. The organization provides emotional and mental health services, including a 24/7 hotline.

In January, the hotline was serviced by 12 counselors a time who rotate throughout the day,

Many of the counselors at the other end of the lines were equally affected as the callers by the hurricane, but that didn’t stop them from coming to work.

“Most of them lost everything,” she said. “The counselors, some of them lost their houses, lost everything, but they were here, working with us.”

When Maria hit, Línea PAS was already in the midst of helping people recover from Hurricane Irma, a catastrophic storm that hit the Caribbean two weeks before Maria.

“People don’t know how to manage their feelings. The potential of suicide in their lives, that’s a thing they’re thinking of,” she said. “We received a lot of those calls during the hurricane, and we’re still receiving them. They’re the most difficult.”

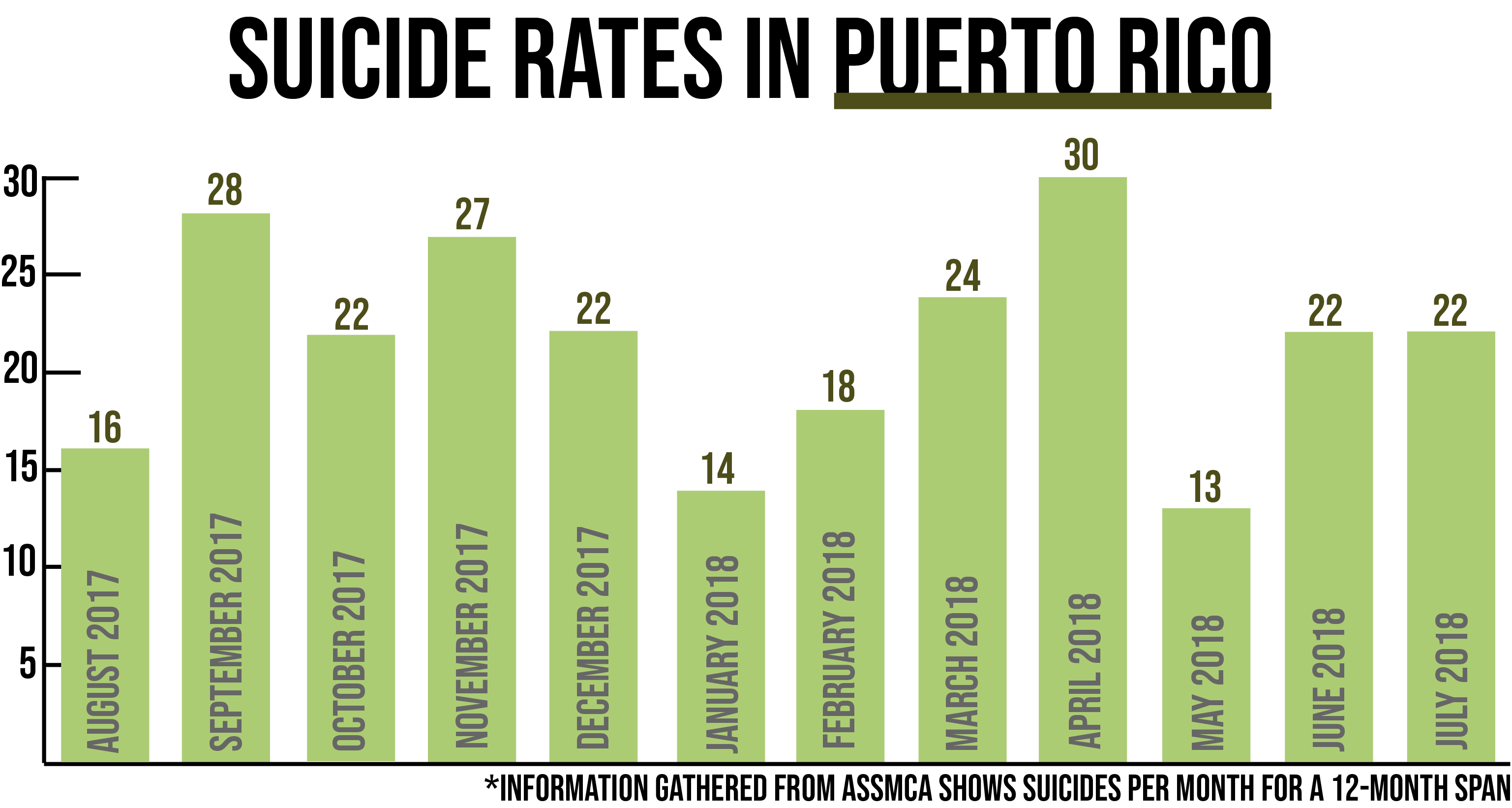

The number of suicides in Puerto Rico spiked to 28 during September of 2017, the month that Hurricane Maria wrecked the tiny island, according to ASSMCA data. The amount peaked, however, in April of the following year at 30 suicides. When Fuertes was interviewed in early January, there had already been 14 suicides in 2019. One was a 16-year-old girl who killed herself the morning of the interview.

Fuertes is proud that people who call the hotline are prevented from committing suicide, “but there are a lot of people that (don’t) call us,” she added.

The government-funded organization hopes to soon find a way to reach those who are in need but don’t call.

“Ask for help,” she said. “Help is out there — you just need to ask.”

People who call the hotline can be counseled to prevent suicide. “But there’s a lot of people that (don’t) call us,” she adds.

The government-funded organization hopes to find a way to reach those who are in need but don’t call.

“Ask for help,” Fuertes said. “Help is out there — you just need to ask.”

Rochelle has lived in her home in Aguadilla for nearly 10 years. A white gazebo dusted with rust sits in her backyard, where two horses graze on overgrown grass. Somewhere on the property, there are 27 dogs, four cats and a parrot.

“They are my babies,” Rochelle says, lovingly.

Rochelle runs “Pitbull Angels Rescue of Puerto Rico,” an organization that works with potential dangerous dogs in Puerto Rico. When the storm struck, 17 pit bulls were in her care and the majority was living inside her house. She lost a number of her babies during the storm and the months after.

After the hurricane, she went to San Juan to seek help from government agencies that were distributing supplies and giving assistance to those in need.

“They promised help — help that I didn’t receive,” she said.

She lost one of her beloved dogs, Sweet Sexy Mama, in the weeks following Maria. Without electricity and help, the dog’s cancer diagnosis was a death sentence.

“I tried to kill myself three times, and the reason that I didn’t is because if I die, who is going to take care of my animals and my mom?” she said. “If I kill myself I am resolving nothing at all.”

In the months following, she thought about taking her own life two more times.

With tears in her eyes, Rochelle recounts a time when she and her mother had been four days without food after the hurricane.

Rochelle had money in her bank account, but with no electricity or internet available after the storm, banks were closed. Without cash, money was useless. As a diabetic, Rochelle was already dying.

She stopped taking her medication because it gave her stomachaches if she swallowed it without water.

Police eventually showed up at her house with a box full of Butterfingers as their only offerings, and without any other option, she ate.

Rochelle says her type 2 diabetes, after a year off medication, is now nearly irreversible.

Her mother, Gladys Gomez, is disabled, with only one leg and severe rheumatoid arthritis.

Gladys remembers the hurricane’s rain penetrating the house, flooding even the bed.

“It was like a war — so many noises. It was roaring, screeching and banging,” Gladys said. “We couldn’t sleep.”

They lost all of their appliances from the sheer amount of water and were forced to use a loan to hire a contractor to repair the home. The Gomezes say he kept demanding more and more money, and finally abandoned the job.

“We have lost trust in many people,” Gladys said.

Rochelle stepped in and tried to repair the house, but she had an accident.

“She’s fallen, and she cut her head. She had to be rushed to the hospital because she’s bleeding so much,” Gladys said. “It was so deep the cut, it to the last layer before the skull, and she’s been having migraine headaches since then. It’s been very difficult, and she needs emotional support. There is nothing I can do but pray.”

Rochelle said she prays, but has lost faith since her prayers don’t seem to make a difference.

“I’m still feeling hopeless, searching for help.”

Some days, it takes Joselyn Rosado four hours to get to and from her university.

“I don’t have any other choice. I have to drive here every day. It’s really expensive, almost impossible,” she said.

A third year graduate student studying social community psychology, Rosado had to move out of campus housing after it destroyed by Hurricane Maria, forcing her to commute to school every weekday. She’s sleeping less and paying more — all to receive an education — but she said the worst of the hurricane’s affects is its emotional toll on University of Puerto Rico students.

A third year graduate student studying social community psychology, Rosado had to move out of campus housing after it destroyed by Hurricane Maria, forcing her to commute to school every weekday. She’s sleeping less and paying more — all to receive an education — but she said the worst of the hurricane’s affects is its emotional toll on University of Puerto Rico students.

“We haven’t had the time to pay attention to what we’re feeling because we’re investing all of our time on the physical work,” she said. “It’s definitely affecting us. We have lost so many things; it’s like we’re grieving, and we haven’t ben able to work on it in an appropriate way.”

She thinks of Puerto Rico in duality now — the place she knew before the hurricane, and the place she saw destroyed by the hurricane.

“Nature is different, the people are different, and the houses are different,” she said, tears in her eyes. “The way Puerto Rico was, it’s not anymore.”

”Nature is different, the people are different, and the houses are different. The way Puerto Rico was, it's not anymore

Joselyn RosadoGraduate student at the University of Puerto Rico Rio Piedras

Luis Agostini Aguiar, a psychologist in UPR’s Department of Counseling, used to often trek to El Yunque National Rainforest, but he hasn’t returned since the hurricane.

“It just isn’t the same,” he said.

Aguiar has worked at the university for five years, and said the surge in students seeking counseling in their department was like nothing he had ever seen before.

There are 57,726 students enrolled at the University of Puerto Rico, and 18,653 of those students are located at the university’s Río Piedras campus.

There are 57,726 students enrolled at the University of Puerto Rico, and 18,653 of those students are located at the university’s Río Piedras campus.

“We received 350 students that first week. (Our department) was working three or four times harder,” he said. “It was overwhelming for the 10 psychologist and counselors we have here. Basically, the first two months were crisis.”

For five months, Aguiar was without power himself. Living on the 17th floor of his building, he had to walk up all 17 flights each day. But he came to campus every day to cater to the students’ needs.

“In Aguadilla, in Aurora, in Caguas, they didn’t have internet. They didn’t have communication. They didn’t have food. They needed communication with their families. It was not only the power situation, but they needed food, they needed counseling,” he said. “They needed to be heard. They were desperate to be heard.”

He said many students kept coming to school because they knew they would receive more help there than anywhere else. He recalled students asking to borrow his cell phone, just to call their family. He remembered a time when a community group brought food to feed 500 students, but they had more than a thousand to feed.

Students dropped out of school. A tree fell and smashed their car. Their parents lost their jobs. Even if they had generators, they may have gone into debt to buy diesel fuel, so they were damaged financially.

“The students got drained and depressed. If you multiply that by six, seven months talking pessimistically about the situation and not knowing how things are going to return to normal, it creates a sense of helplessness,” he said. “You can try to cheer them up, but what’s real is real. Sometimes I had students who had one meal per day.”

Now, Aguiar said, many students with suicidal thoughts seek counseling from his office.

“(The students) have all their necessities now, but the emotional damage, the impact that this created on people, it was huge,” he said. “That’s the help they need now, dealing with depression and anxiety.”

He hopes everything will one day to return to normalcy, but Aguiar doesn’t know when that will be.

Carlalynne Melendez is the administrator of the Naguake indigenous community and director of their schools in Puerto Rico, and her barely three-feet tall Taino students are still afraid of the sound of wind.

“When they hear the rustle of the rain and wind, they’re still living it,” she said. “The shock in their eyes, the way they were trembling — they’re still traumatized.”

“When they hear the rustle of the rain and wind, they’re still living it,” she said. “The shock in their eyes, the way they were trembling — they’re still traumatized.”

She estimates that 90 percent of her students are suffering from post-traumatic shock. After the hurricane, she sent messages to different universities, asking them to send psychiatrists and psychologists, and she didn’t receive a single response.

“We needed a psychologist here to bring back the child in them. They wouldn’t play anymore. They were more worried about what was going to happen to them,” she said. “There was nobody coming to our aid. I felt helpless.”

Instead, Melendez, who is a sociologist and anthropologist, had to double as a psychologist — without training.

“They were telling me about their experience,” she said. “I had to hold back tears because they were pouring out their hearts about losing their grandmother, their grandfather. They had to bury them in the backyard.”

Melendez’s Taino schools are high in the mountains on the eastern side of the island.

“They couldn’t get food up here for four months (after Hurricane Maria),” Melendez said. “They were digging up roots to eat.”

Melendez, who is of Taino descent, was born in upstate New York and moved to Puerto Rico in 2001 to take care of her mother. Her mother was a child in 1928 when Hurricane San Felipe devastated the island. As Hurricane Maria approached in 2017, Melendez said she could tell her bedridden mother didn’t want to experience the horrors of the storm again. On the day the first winds of Hurricane Maria could be felt on the island, her mother died in her arms.

“When we buried her, the winds were upon us,” she said. “I’ll never forget it… it just became dark all of a sudden. I didn’t give her the proper goodbye because the winds came upon us.”

Melendez said the Taino children have helps her cope.

“When I reach the school, they all come running, and that uplifts me — knowing that the culture is going to make them hopeful and give them that will to survive,” she said. “Puerto Ricans, we are people with a lot of strength and endurance. We endure whatever comes, and if we endured Maria, we can endure anything.”

Theresa Renée Eléna Delgado-Tossas met Rochelle post-hurricane doing relief and rescue work. During the rescue of a dog, she learned of the intricacies of Rochelle’s situation.

Delgado-Tossas, involved in a number of nonprofit organization dedicated to relief and recovery efforts for the people of Puerto Rico during times of disaster, was moved by Rochelle’s spirit for service and drafted a proposal to offer Rochelle and Gladys a solar power system.

“(Rochelle’s) really an angel for animals on this island, always doing everything she can,” she said. “Even if she is not able at the time to directly foster, she moves small mountains to help other rescues in whatever (capacity) she’s able.”

Delgado-Tossas has seen cycles of recovery repeat for years on the island, as is the nature of her work, and described it as a “proverbial bottomless pit of mental stress.”

“These types of living conditions, possibly never to be rebuilt, brings such despair,” she said, referring to post-hurricane damage.

She believes the people of the island need job opportunities and fair pay so that they’re able to help themselves and each other — what they always do.

“These incredibly resilient people of the island of Puerto Rico have gone out of their way to help each other get through this aftermath,” she said.

Today, Rochelle continues to battle with her depression and anxiety, often onset by the mere mention of the word “hurricane.” After Maria passed and she received a notification that another storm might hit, Rochelle said she lost her composure.

“Thank God that was dismissed, but I went crazy,” she said. “I started crying, shaking, because I didn’t know… how I’m going to be prepared again for a major hurricane here? It was a horrible nightmare, and we don’t want to live it anymore.”

Rochelle cleans her house every day, struggling to repair the damage that was done.

“If we’re going to be hit again, I don’t know what we are going to do. We need help in here, we definitely need help,” she said. “This is not easy. Maria left too many tracks in my heart — bad ones.”